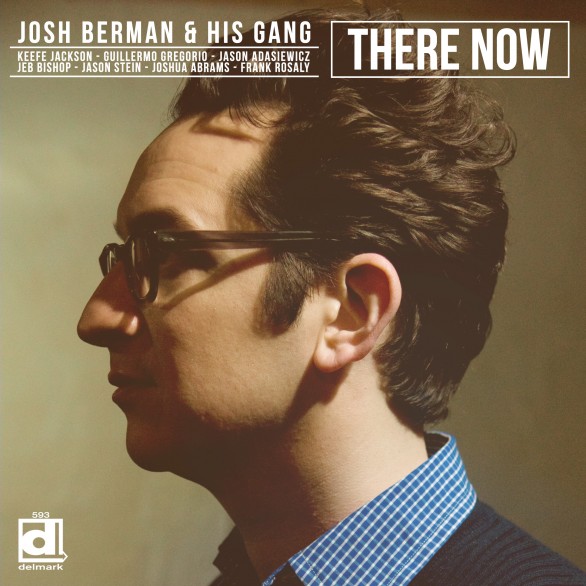

Josh Berman and His Gang

There Now

Josh Berman – cornet

Jeb Bishop – trombone

Keefe Jackson – tenor saxophone

Guillermo Gregorio – clarinet

Jason Stein – bass clarinet

Jason Adasiewicz – vibraphone

Joshua Abrams – bass

Frank Rosaly – drums

And His Gang: that takes you way back, to the 1920s when a few leaders led one—like Perry Bradford, who’d written “Crazy Blues” and run one of the first hot black recording bands, Mamie Smith’s Jazz Hounds; future Hollywood character actor Jay C. Flippen; the forgotten Arthur Gibbs, first to record James P. Johnson’s “Charleston.” And of course Bix Beiderbecke whose Gang updated pieces by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in 1927—a very early jazz repertory project.

For Chicagoans like the players here, the tag also suggests the Austin High Gang, a gaggle of suburbanites (Bud Freeman, Frank Teschemacher…) who’d developed personal and collective jazz styles while working in tandem.

Josh Berman says, “Years ago I got this old collection called Chicago Style Jazz, with a Ben Shahn cover. I was super into that.” That early LP—Columbia 632—spotlighted the 1927 Eddie Condon/Red McKenzie sides like “Sugar” and “Liza” on which four Austinites debuted.

“So I put together a band playing that 1927 Condon repertoire. We did a date at the Chicago Cultural Center in 2007, followed by more writing and arranging, and then the Chicago Jazz Festival in 2008. After that, about every six months, I’d find myself thinking about it a lot. So in 2011, I got more serious about it, writing more creative music, and leaning less on the older material. At this point the band is more about how Joshua Abrams and Frank Rosaly play together, and how that changes with Jason Adasiewicz added. And it’s just as much about how Keefe Jackson and I play together. We’ve all worked together a lot, in all sorts of combinations, like my Old Idea, Jason’s Rolldown, Keefe’s Project Project and other bands. So it feels like a crew.” They often shared bandstands with Jeb Bishop, already a scene fixture when they came up. Jason Stein came later, but made quick inroads; he has a quartet with Jackson, Abrams and Rosaly.

Where the Austin High Gang mostly drifted to New York, Berman’s crew stayed in Chicago, spending long nights jamming at the Hungry Brain and working for various leaders, till they learned to interact in myriad ways. The players have a lot of seasoning on them by now. In that regard this music smacks less of 1927 than Bud Freeman’s 1938 Commodore octet with Condon, Dave Tough and Pee Wee Russell: players with a hard-earned ease of interplay, who stayed true to the music that first grabbed them, while minding changing times. They used old tunes as springboards but modernized the concept. They weren’t kids anymore. They read Proust, even if he was no good in translation.

New stabs at old rhythms are most always anachronistic; later developments leak through. But you can suggest the old beats. Hear how effortlessly drummer Rosaly and bassist Abrams ease between a loose 2/4 and 4/4 on “Love Is Just Around the Corner (Approximately)” and 2/4 swing and free time on “Liza” (Condon’s, not Gerhwin’s). Rosaly is the date’s linchpin—keeps the time moving, and loose, puts a boot to the soloists.

The trad flagwaver “I’ve Found a New Baby” becomes an oddly subdued dirge, as if the players know too well romances don’t always pan out. Abrams, pizzicato, takes the rococo Coleman Hawkins solo, as the band intones the melody behind, to highlight his variations. The bassist’s gravitas, ebony-rubber tone and plosively plush attack are beautifully captured. The middle section honors other Chicago ancestors: the AACMers’ improvised atmo-scapes, free play in slo-mo. When the horns return to the melody, Abrams walks the tune out, just so we can hear how well he does that too. It’s his concerto.

Josh Berman plays cornet not trumpet, so in a sense he always references the ’20s. He mixes thematic variations with purely sonic effects, like Bill Dixon. Or Freddie Keppard. Berman’s improvisations often betray a slippery relationship to the underlying beat—he’ll sliding behind only to play catch up, an old Chicago ploy. (Von Freeman, anyone?) He also has a way of honing a line down to a few essential gestures. Around 3:20 on “Jada,” he’s working variations on a wide-interval wobble when Keefe Jackson starts some friendly heckling, with a more emphatic version of the same figure. Josh’s rejoinder hints at the phrasing of Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz,” which he duly alights on before proceeding—a nice passing conversation.

Jackson’s excitable like that. As “Cloudy” opens he’s charged up even before a Mingusy horn choir slides in behind. “Keefe is such a great changes player, within his own concept,” Berman says. Beat. “I wouldn’t even know what to compare it to.”

As progressive dixielanders turned free players, Steve Lacy and Roswell Rudd knew you can bridge two worlds of collective improvisation. Jeb Bishop’s other gig is as a translator, so he’s comfortable moving between one rhetorical universe and another—not least when some free collective morphs into Nicksielandism or vice versa. He has a way of tailoring the volume and even shape of every note in a fast sequence—“Cloudy” makes his case—and doesn’t stoop to tailgate clichés.

Indeed, the players don’t always take the bait. Berman’s “Sugar” kicks off like 1963 Eric Dolphy with Woody Shaw and Bobby Hutcherson—the date with “Jitterbug Waltz.” (That’s my reading; Josh calls the arrangement “very Broadway.”) Jason Stein on bass clarinet resists temptation to go Dolphectic however: his solo has its own raspy grace, and he gets extra points for tapping Fats Waller’s “I’ve Got a Feelin’ I’m Fallin’.”

One doesn’t associate the vibes with early jazz—the instrument had barely been invented—but Jason Adasiewicz is always welcome. In the rhythm section, he can lurk in the background (hear him behind Bishop on “Love Is”) or stir the pot. Adasiewicz can hit the metal bars very very hard, but the feature “One Train May Hide Another” shows off the pellucid depths of his sound, and his distinctive harmonic voice; chord tones slowly rise through a cloud of bubbles, to light on the surface. “I always heard Adasiewicz playing the melody to ‘Trains’,” Berman says: “It’s his concept exposed.”

That tune takes its title from Kenneth Koch’s fine poem, about how there’s always more to consider, so you should take the time to look. That’s all but Josh Berman’s credo here, as he keeps rolling more and more material into view. His Gang has small group mobility, even in the collectives, but can also supply full-sounding background figures, the trains behind the train. Hear “Cloudy” or “Liza”—or, for gorgeous voicings, the harmonium chords behind the clarinet melody on “Jada.” Josh Berman: “In the longer pieces, there might be an intro, maybe another intro, a theme that can come forward and then recede, passages that work as backgrounds or standing on their own. I love to hear stuff that comes back, followed by still more fresh material, or a background derived from another part of the theme.” His title “Mobile + Blues” evokes Bix’s paean to a Gulf Coast city and the mobiles of Alexander Calder and composer Earle Brown. “But it didn’t end up sounding like I expected. I thought it would be really quiet.”

The Gang’s apparent ringer is clarinetist Guillermo Gregorio, the Argentine composer resident in Chicago, rather older than his bandmates. But he has the most direct connection to the material, having identified with the Austin Gang early. “There are ‘scholars’ who say that ‘Chicago style jazz’ never existed,” Guillermo says, “but growing up in Buenos Aires we knew better! I got my first clarinet as a teenager after listening to records by Johnny Dodds and Pee Wee Russell. Since then, I’ve gone through many things, musically speaking—musique concrѐte, free jazz, non-jazz improvising, the Fluxus movement, graphic scores, visual art and design—which may influence my playing now, or not. Josh never told me how to play in the Gang, but the peculiar conception of his arrangements was not that far from my own interests, and I discovered new aspects of that old music.”

This new music is at least partly about how old music gets remembered—how our memory shapes our reality. Gregorio plays the bridge of “Love Is Just Around the Corner (Approximately)” from memory, an act of creative reconstruction: imperfect, but just perfect. But that number is about forgetting too—the pedal-point intro that keeps restarting is so flashy, they never do play the main theme. The old numbers endure because they’re never played the same way twice; they can always be reinvented.

Josh Berman: “All these musicians are really good free improvisers, and I want to feel that all the time when we play. But they all know how to play the blues too, each in their way. Every part on every piece was constructed with these guys in mind, down to which backgrounds go with which solo. After we recorded, I worried how inside and controlled some of it turned out to be, but you have to let things be as they are.” Gotta give your improvisers leeway when they come tumbling down the gangplank.

–Kevin Whitehead

author of Why Jazz? A Concise Guide (Oxford)